The following explores the financial ramifications that can result when senior partners, who are typically the biggest billers in most law firms, begin to retire in large numbers—and some steps firms should take starting today in response. With some proper planning, firm mindedness and a good bit of luck, the firm will be serving clients long after today's partners retire.

Understanding What's at Risk: Digging into Revenue Streams

In assessing the financial risk to the firm, the first step is to understand the firm's revenue stream, in terms of the percentage of revenues that senior partners typically generate in comparison to more-junior lawyers. As an illustration, let's take a firm where all partners generate combined revenues of $8 million. Let's also say this firm has a formula-based partner compensation system in which every hour delegated to junior lawyers has a negative impact on the partners' personal earnings, so over time the middle of the firm has eroded.

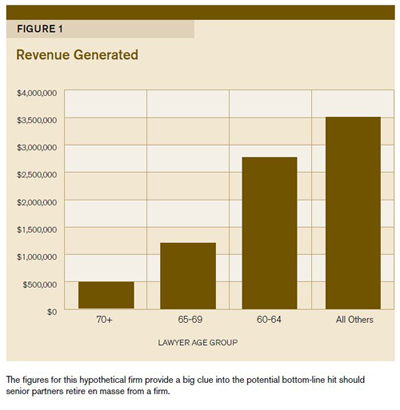

Next, let’s look at how this sample firm’s revenues are generated by age group, as shown in Figure 1. Those under the age of 60 represent less than half of the total revenue, at $3,500,000. The partners who are over the age of 70 represent the smallest percentage, with $500,000, so if they leave tomorrow, the impact on firm revenue won’t be too immense. But what if the partners between the ages of 60 and 64—who bring in $2,750,000 of the total revenue—decide en masse that it’s time to retire?

Next, let’s look at how this sample firm’s revenues are generated by age group, as shown in Figure 1. Those under the age of 60 represent less than half of the total revenue, at $3,500,000. The partners who are over the age of 70 represent the smallest percentage, with $500,000, so if they leave tomorrow, the impact on firm revenue won’t be too immense. But what if the partners between the ages of 60 and 64—who bring in $2,750,000 of the total revenue—decide en masse that it’s time to retire?

To fully analyze what’s at risk, law firms will need to delve into their client base to understand the depth and breadth of the firm’s overall relationships with clients. As you do so, think in terms of what the client’s business means to your firm in terms of revenue today and the potential for tomorrow. Here are some key questions to consider:

- What work do you do for this client? How many practice areas, or how many individual lawyers, currently serve the client?

- How many people in the firm have a relationship with this client?

- If the client is a business, will the business wind up when its owner retires? Or is there a next generation preparing to take the helm—and if so, who in your firm is the logical fit for the relationship going forward?

- What specific steps can you take to shift the relationship to the next generation in your firm?

If the firm’s primary revenue stream comes from individuals who mostly require one-time services or only occasional legal advice, which is common for small firms, you may have a tougher job understanding and predicting your client base’s potential revenue stream. Consider the revenue by practice area:

- What areas is the firm known for, and how do lawyers in the firm attract clients who need such services?

- Who are the key referral sources, and how many people in your firm know them?

- If the senior partners get business by networking in certain industry groups, local associations or service clubs, are there younger partners or associates in your firm who are also involved in those groups?

A critical part of this analysis is understanding which of the firm’s competitors will be “chasing” key clients if the current relationship partner leaves. This should help lend a sense of prioritization from a flight-risk perspective.

This in-depth analysis should probably be the work of the firm’s senior financial administrator— one who knows the client base and the lawyers well—and it should look at trends over the past three years. By clearly understanding the client base and its retention prospects under the current lawyer-client relationships, you will have a much better understanding of the risks and opportunities for the firm going forward.

Ingraining Practice Transitions in the Firm’s Planning

Despite the prospective financial threats presented by senior partners’ departures, the real status quo in many firms, particularly small and midsize ones, is that there is no policy as to how and when clients should be transitioned. But it’s clear that without the transfer of client responsibility to the next generation, the firm’s financial prospects may seriously erode.

The long-term sustainability of the entity necessitates that the orderly transition of clients from senior to junior lawyers become an ingrained part of client-relationship planning. That includes taking steps like these well in advance of a particular partner’s actual transition period:

- Establishing more than one contact point both at the relationship and the service levels with clients

- Including delegation of client work as a fundamental compensation criteria

- Talking openly to the clients at appropriate points about the coming need for succession planning on their work files

Of course, the trickiest part may be getting senior partners to buy in to the process of transition planning for their practices. This requires reaching a firm-minded consensus over the fact that when partners retire without a plan, it can pretty much guarantee a slow evaporation of their book of business and the quiet erosion of the firm’s revenues. Retiring in spirit, if not in fact, and without telling anyone has the same effect: The partner gets dressed, goes to the office, goes through the motions but the long slow disengagement with colleagues and clients can be equally disastrous.

To retire with a plan, partners need to be prepared to have the conversation. It is often a difficult conversation, fraught with emotion, apprehension and even fear. But whatever the obstacles, law firm leaders need to open the lines of communication among the partners. (See the articles by Marcia Shannon and Tom Grella in this issue for more advice on holding these discussions.) However, a particular stumbling block that frequently arises in laying out transition plans for equity partners is how it will affect their earnings, and when that impact will begin. Let’s turn to that critical issue now.

Addressing Compensation Questions with Equity Partners

Most compensation systems don’t effectively or fairly address how practitioners will be compensated when it comes to transitioning out of equity status. As one partner eloquently put it, retiring partners are expected to be “philanthropic.” This is especially true of objective or formula-based systems, which generally combine personal productivity and books of businesses in calculating compensation (or value to the firm).

Unfortunately, this leads to the main obstacle to successful practice transitioning—the conflict between the partner’s desire, or need, to earn a certain income level and the firm’s need to have client relationships successfully transferred to younger partners.

Successful transition arrangements require open and direct dialogue among partners that reaches consensus on several key points:

- Retirement Date. This is the date at which the lawyer will cease to be an actively practicing equity partner. This doesn’t preclude the lawyer continuing in an of counsel role (or an alternate nonequity position) after this date, subject to the firm’s approval.

- Length of the Transition Period. This is the length of time, in months or years, over which the orderly transfer of clients and work to younger partners should take place, the goal being that all principal client responsibilities are transferred in advance of the retirement date. There are no “cookie cutter” solutions here, which means the transfer arrangements must be adapted to the given practice and practitioner in transition.

- Compensation and Evaluation Criteria During the Transition Period. During this period, it’s critical that the partner transitioning stays in the “normal partner” compen-sation scheme. However, since the partner’s client responsibilities and corresponding workload is expected to decline during this time, the firm should have additional evaluation criteria for things apart from billable productivity in support of the transition. For example, some partners’ transition plans may specify that, as of a given point in time, they are to have no more than 40 percent of the total time on any given file. Those who meet that number are clearly delegating the bulk of the work to others according to plan and that behavior should be rewarded in some way. Those with more than 40 percent of the total time on active files, on the other hand, may need to be penalized.

- Post-retirement-date expectations . Lastly, there should be up-front discussion about what the transitioning partners can expect from the firm in the post-retirement phase. If, for example, the lawyer will stay on in an of counsel role, the parties need to be clear about the time frame for it, the compensation involved and the office space and staff support that will be available under the new arrangement. Expectations concerning medical and similar benefits should also be discussed with all retiring partners, including how the coverage will change and who pays the premium beyond retirement.

Paying Out Capital Contributions

A final issue in planning for the departure of equity partners is the corresponding payout of capital to them. The terms of the partners’ agreement, of course, will vary across firms, but for more than a few firms the need to pay out capital can present a significant cash flow issue. Careful advance calculation of the payouts that will be needed during given timeframes can and must be part of the firm’s financial forecasting.

Notably, the pay out of capital is one argument that supports staying on as counsel for a period of time after retiring from the equity partner ranks. From the firm’s perspective, these retiring partners have a vested interest in working with and for the firm to generate sufficient revenue and cash flow to pay themselves out. In other words, negotiating the time period over which capital may be paid out can assist in an effective and smooth transition period, since it’s one way of augmenting a partner’s cash flow during the winding down of the practice—and it also smooths out the potential cash crunch that can result in the firm from paying out lump sums.

Everything you can do to plan out the cash flow requirements involved in equity partners’ departures will be important to the financial wellbeing of both today’s and tomorrow’s partners—and to the sustainability of the firm itself. Remember, practice transitioning is ultimately about how the firm survives the storm of the generational shift.